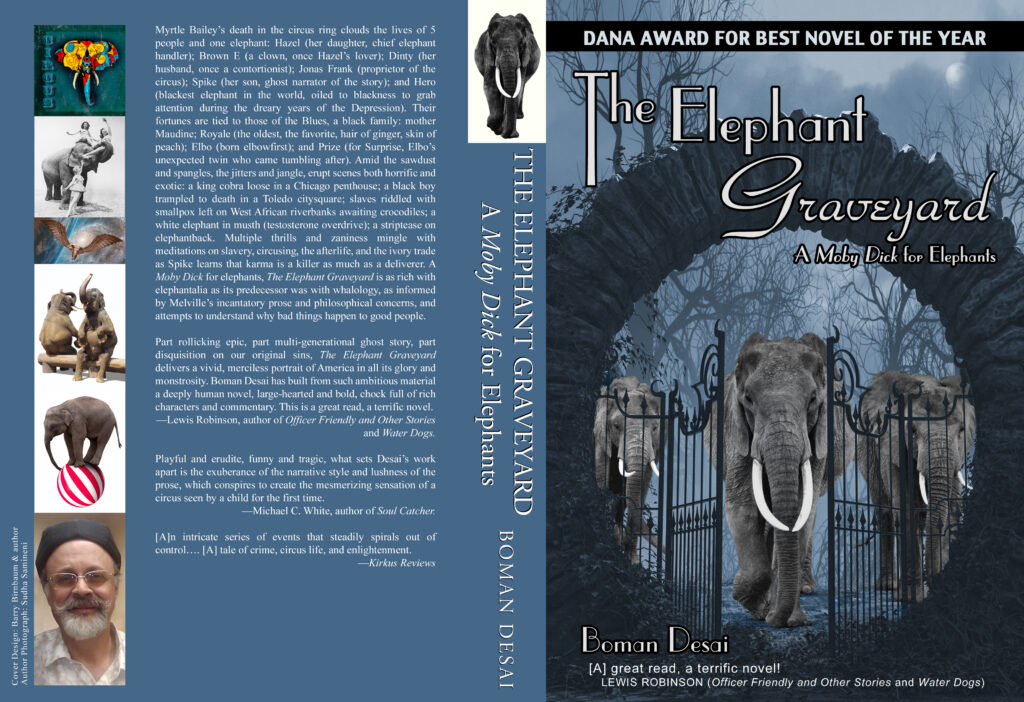

THE ELEPHANT GRAVEYARD

A Moby Dick for Elephants

For the longest time my two cultures, Indian and American, merged only in dreams. I looked continually for links between the two in my writing, but the immigration theme had long been flogged to death (thirdworlders with one foot on a dirt track, the other on an escalator), not least by myself, and I wanted to find another way. Strangely (or not so strangely), the elephant suggested itself as an option: an Indian elephant in America to link my two cultures.

It is the favourite animal of many, including myself, but only in an academic sense, a favoured status that invites neither the risk nor sacrifice of a bullman, handler, or mahout. As a boy, I’d had elephant cufflinks, bookends, lamps, patterns on curtains and bedcovers among other such elephantalia. For my Navjote I’d asked for a wooden elephant two feet tall. The mother of a friend once called my mother to say I’d spent the afternoon drawing pictures of elephants. My first published novel was called The Memory of Elephants, but the title was a metaphor for long-term memory, nothing to do with the great grey beast itself—with which I’d had little contact except at the Bombay zoo where I’d ridden the mighty animal’s back.

To begin I knew only that I wanted an elephant to be central to the plot. To that effect, I researched elephants thoroughly, settling first on a zoo to springboard into the body of the novel—but the circus soon suggested itself as a more colorful alternative. I researched circuses no less thoroughly, even visiting circus grounds to get a feel for the place. Casting my net for novels centered around single animals, I landed Moby Dick. I reread the classic and Melville’s incantatory prose raised the bar for my own, I filleted my novel with elephantalia as Melville had his with whalology, and Melville’s metaphysics opened the door to mine.

A photograph in a National Geographic of a man lifted by his head in the mouth of an elephant gave me the central plot. My outsider status also played into the novel. I am fairskinned enough to surprise people when they learn I’m from India, but I was called the N word on a couple of occasions leaving me wondering how many times it might have been thought and left unsaid. I knew I wasn’t being mistaken for a black, I also knew I was being verbally slapped for my ethnicity. I don’t mean to say my blues are bluer than the blues of blacks, they’re not by a wide margin—but, whatever my advantages, I was disenfranchised in the US—and too dumb to recognize it for decades because I wanted parity with the majority. As a Zoroastrian Parsi, I am swept in the current of the American soup, too small a minority to be considered a minority—or, indeed (fortunately), oppressed as a minority—but enough of a minority to be isolated, different, other, alien, to be tolerated, even indulged, until day is done and it’s time for the majority to return to the root, their aria of patronization drawn to a close. This is not a complaint; without my rootlessness, I might never have written The Elephant Graveyard; it is the way of the world.

Also, educated as I was in India, a stranger to American history, I had imagined racism as much a relic as slavery in Twentieth Century America. I was surprised to learn Civil Rights were not even a decade past when I arrived (1969), and my research uncovered events too heinous to mention. I won’t dwell on my problems with assimilation, but a large difference between me and almost everyone I knew was that in America I was sans family, sans community, sans ground beneath my feet. This played well into the structure of The Elephant Graveyard, but more subtly than the common theme of a stranger in a strange land. The supernatural element is also a variation on the theme of the outsider (the tale is told by a ghost), a specter being even more of an outsider, an isolate, than an Indian or a black.

Serendipitously, my research opened the door between the elephant theme and racism. The nineteenth century saw Arab strongholds established with gardens and homes and harems in the African interior, and once the Arabs obtained firepower they took what they wanted without pretense of barter, enslaving the very Africans from whom they stole ivory to force them to carry the booty to the coast. One in ten survived the march only to be sold alongside the ivory, making the ventures doubly rewarding, a trade in white gold and black, ivory and slaves, the two were one. Once the gambit proved successful the slaughter commenced a hundredfold—and with the Europeans it continued a thousandfold.

The most trenchant of the novel’s themes, Enlightenment, comes clear only toward the end (a ghost narrator being privy to the afterlife like no other). This most abstract of themes is framed within the most concrete contexts: the story roars through the pages like an avalanche. Myrtle Bailey’s death in the circus ring clouds the lives of 5 people and one elephant: Hazel (her daughter, chief elephant handler); Brown E (a clown, once Hazel’s lover); Dinty (her husband, once a contortionist); Jonas Frank (proprietor of the circus); Spike (her son, ghost narrator of the story); and Hero (blackest elephant in the world, oiled to blackness to grab attention during the dreary years of the Depression). Their fortunes are tied to those of the Blues, a black family: mother Maudine; Royale (the oldest, the favorite, hair of ginger, skin of peach); Elbo (born elbowfirst); and Prize (for Surprise, Elbo’s unexpected twin who came tumbling after). The straightest line runs from the death of Prize at the hands of Spike to Spike’s sacrifice of his own life for another as he comes to terms with the meaning of life. To learn more about the novel and its author, please visit www.bomandesai.com.