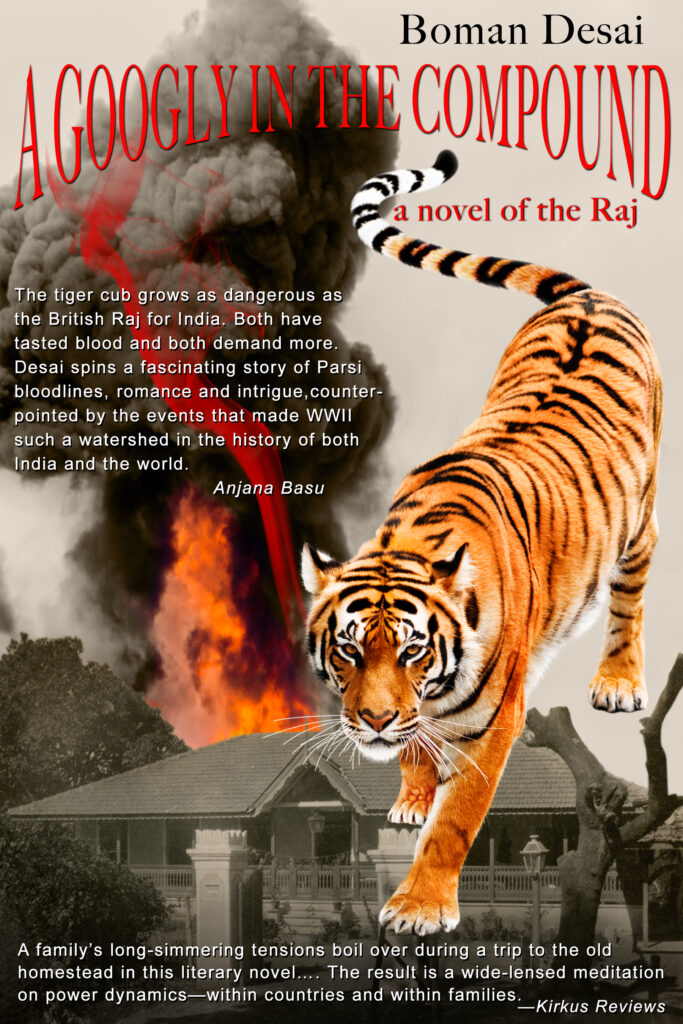

A Googly in the Compound

(A Novel of the Raj)

Boman Desai

My bapaiji, who lived in Navsari (200 miles up the coast from Bombay), was a great storyteller. When my brother and I paid annual visits during Christmas holidays, the three of us would crawl into her wide mosquito-netted four-poster bed every night. She would lie on her back between us and launch into tales from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Shah-Nama, Arabian Nights, Hans Christian Anderson, and Brothers Grimm among others—or she would make up stories. She knew how to stretch a tale, how to conclude with a cliff-hanger, much like Scheherazade even without the threat of the sword of Damocles.

She once related the story of a shikari who had bagged a maneater and brought home its orphaned cub to raise as a pet. No larger than a kitten perched on the back of his hand like a glove, the cub soon grew to 150 pounds. Waking once from an afternoon nap in his armchair, the shikari found it licking his hand, opening a cut sustained while shaving that morning, relishing the taste of blood. When he attempted to remove his hand, the cub growled, and he realized it might pounce, even maul or kill him if he got too proprietary about his hand—and called his servant to shoot the cub.

The story stayed with me, becoming gnarled and tangled with time. The hunter developed into a solicitor and his family, the family developed a history, their servant developed a grudge, and I provided him with an opportunity to feed his grudge. I cannot say how many of my decisions were conscious, how many unconscious, but I started with my bapaiji’s story of the shikari, I added a woman to complicate the issue between servant and master, I made her English to highlight the differences. New episodes swam continually into the narrative, individual stories of the characters falling in place once the long central scene with the tiger was settled. The mosaic became increasingly clear as I researched elements of the story with which I was unfamiliar: astronomy, coelacanths, the Kut campaign, London between the wars, the communist party in India—but the novel, first published under the title, Servant, Master, Mistress, was nevertheless published prematurely. One of the major characters did not have a story of his own.

I had exhausted my imagination and rationalized that he was too effete to have his own story—until a friend of my mother told me about her father. She had been 13 and the family living in Rangoon in February 1942 when the Japanese invaded. They were sent by boat, hugging the shore to Chittagong where they boarded a train, then a ferry across the Brahmaputra, and finally another train to her uncle’s home in Calcutta. They might have taken the boat directly to Calcutta from Rangoon across the Bay of Bengal, but the Bay was then lousy with German U-boats.

Her father, a doctor, was held back by the British to help fight epidemics during the retreat, but left finally to find his own way out of the country. He was stopped by four British tommies along the way who commandeered his jeep, leaving him to negotiate a journey of about 900 miles afoot.

Astonishingly, he found his way to Calcutta amid tens of thousands of refugees who died along the way, arriving at his brother’s flat more dead than alive himself, only to have the door slammed in his face by his sister-in-law, too scared by his appearance to recognize him.

His story had a happy ending, but not that of the 4 tommies who’d stolen his jeep. He came across them again during his walkout, still in their seats, throats slit. More to my purpose, his story provided the final stone in my mosaic. I saw my supposedly effete character in Burma and began researching the campaign. Learning that the 17th Indian Division had been formed in Ahmednagar, I realized that would be his point of entry.

On a superficial level this is a colonial novel and colonialism may seem outdated in a postcolonial world—but on a more profound level colonialism provides the clothing for themes of race and class, master and servant, cause and effect as ineluctably as postcolonialism. These are themes longer lasting than their clothing, longer lasting than either colonialism or postcolonialism. Colonialism is with us today, illustrated among other things by the unrepresentative incarceration of blacks and Hispanics in the US, healthcare and tax systems unabashedly favouring the wealthy, bankers and brokers exonerated of grand larceny, and presidents of manslaughter in the name of war against countries helpless to assert their rights.

The book encompasses a vast panorama including scenes in which a monkey exposes a yogi’s “spirituality,” a 10-year-old English girl seduces an 9-year-old Parsi boy, two lovers escape to India from Stalin’s Soviet Union, a young Englishwoman meets her first lover at the Silver Jubilee of George V, and a soldier meets with tragedy during the Kut-al-amara campaign of the Great War. Threading these and other stories is the long central scene, taking place in the compound on 25 September, 1945, climaxing in a confrontation with an enraged tiger. The story spans the years from 1910 to 1945, and the globe from rural Navsari to cosmopolitan Bombay to 1930s London to war torn Burma and Mesopotamia, both World Wars playing a role in the plot. Like The English Patient and Corelli’s Mandolin, A Googly in the Compound is a story of love and war and should appeal to admirers of those novels. It is also a Raj novel with a difference: the perspective is Indian, more particularly Parsi, not British, which makes it unique in the annals of Raj novels.